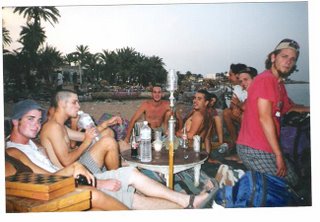

Dahab 1997.

Dahab 1997.Bali, Sharm el Sheikh, Casablanca... Dahab is one of about a dozen tourist enclaves that have been targeted by islamofascists over the past decade or so. It seems apparent that among the list of things that Al Qaeda and their ilk don't like is people having fun, especially people of different faiths having fun together. "Don't like" hardly does justice to the motivation behind the design and execution of a synchronized attack that takes the lives of 30 civilians, but in simplest terms, "don't like" is what this is about.

For most of us, when we "don't like" something, we write our congressmen, go on TV, start a blog, bitch about it with our colleagues at the water cooler, or something similar. Barring that, we take to the streets. When there are no congressmen, two crappy channels on the tube, limited internet, no work and a consciously divisive governing elite that's more than happy when their subjects "don't like" something other than themselves, other outlets seem to channel all that "don't like" energy that we all have. When there are few avenues for frustrations, people who really, vehemently, mortally "don't like" something all of the sudden seem louder, more important, even righteous. In the worst cases. we get bombings and death, all with the tacit approval of the world's dictators, and most elected officials as well.

For me, there was little I could say that could constructively add to the chatter about terrorism until something personal interjected. 9/11 got personal and I wrote about that but shut up after catharsis was achieved. Everything else had been lunged upon by more compulsive and eloquent people than myself. To write more about 9/11 would have been like beating a dead horse that had been magnificently slaughtered, disemboweled, quartered, and shipped to French dinner tables.

But like Washington, New York and Pennsylvania, I'd been to Dahab. When I first went there, I'd been living in Israel for about 6 months, just out of high school. We were on a program that had a group of us volunteering on a kibbutz doing mostly agricultural labor when we weren't partying, breaking (or burning) stuff, having deep, meaningful experiences with our peers, or being subjected to occasional indoctrination towards a set of left-leaning zionist principles. Shifting from "I" to "we" here is a conscious decision. I've never felt like more of a group in my life. Say what you please, but the reality of this was that of a group of 18- and 19-year-olds with little to no supervision in a remote part of the world. It was both a silly and an intensely powerful time.

Part of being on a kibbutz as a volunteer is to be surrounded by the comings and goings of backpackers with their enviously smug lore about where the best parties are. Dahab was where the party was at, and getting there was no harder than hitchhiking down to the Israel-Egypt border, crossing over and hailing a taxi. Before ever going there, Dahab became an oft-discussed part of our group's mythology, forbidden by the program under penalty of expulsion, and all the more alluring. It conjured imagery of a bedouin oasis, or maybe just a mirage.

The first time a few of us went, we told no one except for an inner circle of people that we were going to leave the country for a land of mystery. The official story was that we were hitchhiking to Tel Aviv to stay with someone's uncle, something that people did all the time. We even managed somehow to con our passports from the clutches of our supposed supervisor Pam, a somewhat loathsome alumna of our program turned Israeli who was tasked to watch over us. Our main concerns were 1. that someone would bother to look at the fresh stamps in our passports, or 2. that something would happen there or in Israel that would require the obligatory phone call to declare that we weren't somehow involved in the occasional killings and dismemberments of the region; something that we might not even hear about, sitting on the beach as we would be, away from newspapers, and slightly before the internet's hostile take-over of all matters of daily life. These were acceptable risks. Dahab had to be seen with our own eyes.

The 1996 Lonely Planet edition, Middle East on a Shoestring had an entry on Dahab that really got to the core of what traveler life was about. That entry affected my thinking on what was out there to see and do more profoundly than I'd realized at the time. I still remember it fairly well. Paraphrasing over 10 years of memory, it went something like this,

"Dahab is one of those few locales peppered across the world where travellers have gravitated for years with the understanding that the pace was relaxing, the expenses minimal and the drugs copious. Aside from world-renowned diving and snorkelling of the colourful and aptly-named Blue Hole, Dahab offers an appealing rest for travellers arriving from the bustling commercial centers of Cairo or Tel Aviv. Tourists are invited (or coerced) to recline on overstuffed pillows by the seashore, eat from almost identical menus, and partake of the delicacies enthusiastically offered by their Bedouin hosts. Expect a pizza to take three hours to arrive... Accomodations range from straw huts for around 10 Egypytian Pounds (US$3.33) to moderate-to-high end hotels and resorts one would expect in a larger settlement. Must-see nightlife can be found at Crazy House, the Al Capone, Aladdin Cafe, and many other lazy spots to dance to reggae with people from many walks of life."

Getting there was to bear witness to the world-wide party that had been burning the eternal flame since they invented fire. Places like Dahab are a cross-roads for so many different people that they serve our humanity, and teach us about the basic things we have in common. Joking, food, games, water. Going to Dahab was nothing like the euro-rail experience of partying with diverse fratboys, rugby thugs or misguided alcoholic Finns. In one night I hung out with a Turkish guy named Ahmad, two Sudanese, rasta-types, one Egyptian kid named Masheen who spent most of his childhood in California, a slow and strange English guy named Simon, endless Israelis, Bedouins, Mainland Egyptians, Canadians, Chileans, Americans, Australians (of course), a handful of Yemeni cab drivers, and who knows who else. I know of no other place where this happens. I'm sure that more than a handful of these people go on to be ambassadors, diplomats, peacekeepers, or to fill other positions of power. You have to start somewhere, be inspired by something.

My clearest memory of Dahab is arriving for the second time. We were at the beginning of a two-week trip to the Pyramids, Luxor, Aswan and points between, ready to try travelling (with two l's). After about 6 hours of transit, hassles at the border, and a mysterious "border tax" requested once our taxi was in the middle of stark desert. Our driver looked like Yassir Arafat, complete with kfia and stubble. We nicknamed him "penis", because of his vague resemblance to penises, and the coarse way he did business. My friends from the program, Ben and Nature Boy had already been in Dahab about 10 days when we arrived. They'd decided to leave the program early because they were tired of the hassles from Pam, who managed to spend most of her interactions with us horrified by our behavior, and not really doing anything about it. With hindsight, that Ben and Nature Boy just left and split the country is a testament to her squalking powerlessness. Walking down the dusty main road, along the strips of primative restaurants, palm trees and Sinai coast, the two emerged from a flock of people. They were shirtless, dark as Nubians, and encircled by a group of Bedouin children who paced them like flies and cats, smiling. We hadn't had any plans on how we'd find them. No emails, nothing discussed. We just knew we would. We were "we" after all. The last thing that comes back from this chain of events is Ben saying with his ingeniously wry simplicity, "come with us. we've got the spot." Travelling.

It must be said that Dahab wasn't the best place on Earth, even as a 19-year-old with little direction. It was hot, mosquito-ridden, full of Egyptian hustles and hassles, but it was free from almost all constraint. All you did was find a comfortable spot on some pillow, and take what comes. Dahab was (and is) one of the only places in the world where travelers from Islamic countries meet Israelis, have dinner, and play backgammon with each other into the night. They really made friends with one another, the same as anyone else might. All of the Bedouins, including young children spoke Arabic, Hebrew, English, smatterings of Spanish, Italian, French, German and other languages. They wanted to make money, and to be good hosts, not necessarily in that order. Being so remote from the tense capitals to the north and west, Dahab followed its own rules. As we found a few days later, the Sinai had little to do with the abject chaos of mainland Egypt, wonderful as that was. Dahab tapped into the inherently psychadelic aspects of Arabic culture; the subjectivity, the deadpan mañana attitude, the shifting, complex and gossamer realities that I've found every time I've traveled to an Arabic-speaking place, or been around the people. For 19-year-old me in 1997, Dahab seemed like the future of middle-eastern relations pioneered by brave hippies from both sides of a narrowing, though still vast divide. Seeing people just relaxing and having fun made all of the discussions about Arab-Israeli conflict almost moot. This silly place was part of a larger cultural solution to endless suffering and horror.

I was listening to NPR in the car when I heard about the bombings in Dahab. The Aladdin Cafe was mostly destroyed, and the current mixture of rarified, diverse and ever-changing people present at the time had literally been disintegrated by hatred. I yelled fuck and spastically punched the car's ceiling. It's just too easy to screw up a good thing.

People attacked Dahab because they "don't like" something going on there. They "don't like" it to the point of justifying murder. I'll put aside for a moment the bumbling, callous manner with which this "don't like" problem has been handled by my government, I'll forget about our own sectarians who call for responding to genocidal acts in kind. This is a horrifying set of beliefs that are pushing us further from the backgammon table and closer to the trenches. Dahab was a vision of the peace and modest prosperity that people make on their own, when powers are far away.

It's upsetting to me when something like this becomes misconstrued as some shift in geopolitical balances. Speak on those terms if it's useful, but remember that to have stood somewhere where an attack has taken place is to see people in pieces, to hear sirens and screams, and to smell sweet-and-sour smoke and gore. It sticks around as thin, indelible lines of reddish-brown in sidewalk cracks, on the walls of buildings, in older people's wrinkles.

I have a picture of me and a friend on a hillside overlooking the Valley of the Kings about a week after we met up with Ben and Nature Boy. We walked down from there and spent the afternoon exploring the tombs of ancient Pharaohs. That hillside is the place from which gunmen charged downwards to ambush a group of tourists at the Temple of Hatshepsut in 1998, killing over 60 people because they didn't like something they were doing, or something they seemed to symbolize. Thinking a little further, that whole trip which started at the Egyptian Border, and ended in Tel Aviv two weeks later was both a tour of the magnificent creations of humanity, and a site-by-site tracing of violence past, and violence to come.

It angers me that we've allowed these ideas and the environments that promote them to fester for so many years, on so many people's watches. Knowing the horrors of history, it is negligent homicide for any leader to ignore this or to use it for his limited advantage. Maybe these problems may only be solved by real people, really meeting each other, fighting the bigotry of isolation. I'll go back to Dahab and play backgammon with anyone, any time.

That's what I can do for now.